Alternative Applications CASE 1 “Upcycling Cacao Husks”

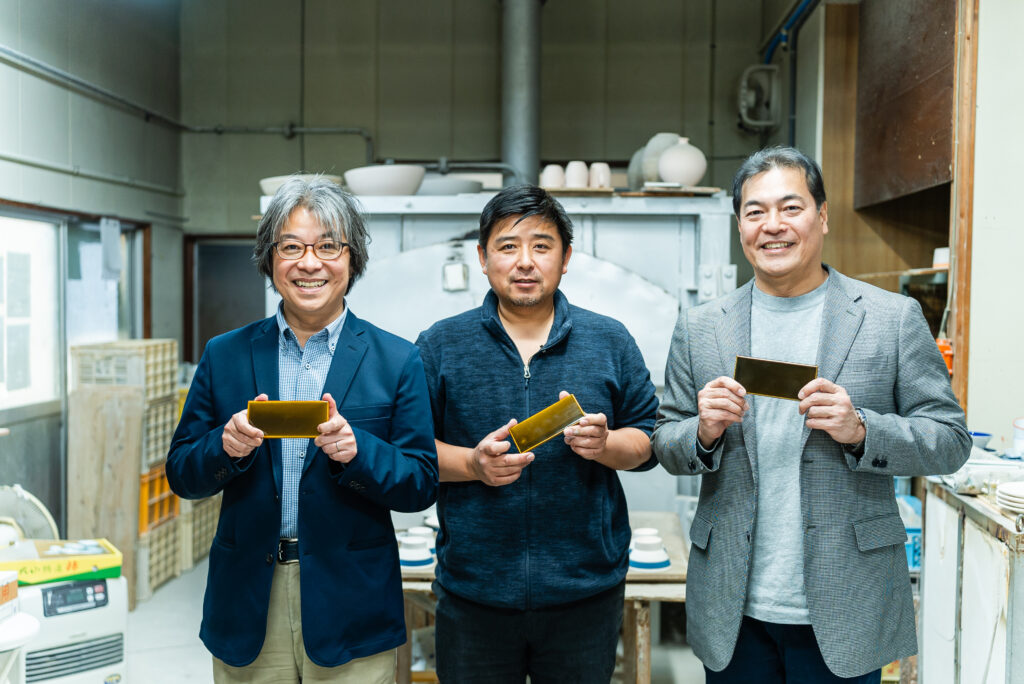

In December 2022, Hydro PowTech Japan Co., Ltd. entered a strategic alliance with Lotte Co., Ltd. to “create new value and solve social issues through technological innovation and upcycling, primarily in the chocolate industry.” One of our challenges was identifying ways to use cacao husks – a byproduct of chocolate – in ceramics. In this article, Lotte Executive Officer Hiroaki Ashitani and our President and CEO, Kumazawa, visited Ohnishi Ceramics in Tobe Town (Ehime Prefecture), where we co-produced cacao husk ceramic tiles. After touring the kiln, we sat down for a conversation with Mr. Ashitani and Ohnishi Ceramic’s President, Mr. Ohnishi, while viewing the ceramic prototypes.

Lotte Corporation

×

Ohnishi Ceramics

×

Hydro Powtech Japan Co. Ltd.

Kumazawa: At Hydro PowTech, we’re collaborating with Lotte, a confectionery manufacturer, to upcycle cacao husks, one of the byproducts of chocolate-making. This new project aims to add value to something we’ve discarded and give it back to society in a useful form. Mr. Ashitani could you start by explaining what cacao husks are?

Mr. Ashitani: Cacao husks are the shells of cacao beans. In chocolate making, you roast and crush the cacao beans, separating them into cacao nibs, which we use to make chocolate, and cacao husks, which we can’t use. Due to our large chocolate production, Lotte produces several hundred tons of cacao husks annually. We’ve struggled to find an effective way to utilize these cacao husks.

Kumazawa: That’s an enormous amount. Considering that Lotte is one of Japan’s top chocolate manufacturers, it’s inevitable that you’d produce such large quantities. How have you been disposing of them until now?

Mr. Ashitani: We’ve been using them as agricultural fertilizer and animal feed, but they’re not as profitable as we’d like. By teaming up with Hydro PowTech Japan, we hope to give cacao husks a new role, one with added value and hope to inspire and surprise our customers.

Kumazawa: Yes. Although our hydrolysis technology allows us to use cacao husks for food, it’s not feasible to process them all in that way, given the scale of the quantity you’re speaking of. This led us to try to reuse them in ceramics as part of our efforts to explore new upcycling methods.

Mr. Ashitani: It blew my mind when you mentioned turning cacao husks into ceramics. Since cacao husks come from a seed that grows in the soil to become a tree that eventually bears fruit and produces these shells, this idea aligns with your concept of “returning to the earth,” which you mentioned before.

Kumazawa: Yes, it’s vital that we return what comes from the earth to the earth, and if we’re doing that, we could create something durable. It would be a waste if it broke down quickly and turned into garbage.

These ideas led us to Ohnishi Ceramics – a kiln in Tobe, Ehime Prefecture – to help us make long-lasting ceramics. Tobe is known for its beautiful ceramics, such as the traditional Kurawanka bowls.

We sent Ohnishi Ceramics hydrolyzed cacao husk, a fine powder created using our hydrolysis technology. They mixed this powder into the glaze for the ceramics. Could you explain what glaze is, Mr. Ohnishi?

Mr. Ohnishi: Glaze is the shiny, glassy coating we use on the surface of ceramics. We apply it during the initial firing stage, and it turns into a glass-like layer when baked, making the ceramics durable and preventing water from seeping in.

Kumazawa: The components in the glaze also affect its color and texture, right? What are your thoughts after using the hydrolyzed cacao husk?

Mr. Ohnishi: Yes. Initially, I had never seen cacao husks before and didn’t understand their properties, so I asked a public organization, the Ehime Research Institute of Industrial Science and Technology, Ceramics Research Laboratory to analyze their components. After that, I tried mixing them into the glaze. Since cacao husks are organic, they burn off in the kiln.

So, I began investigating how much of the cacao husk remains after firing. In the first stage, I mixed raw, powdered cacao husks into the glaze, but it didn’t work well because of the husk’s high oil content, which the clay absorbed most of. Next, I tried burning the cacao husks to ash and mixing the ash into the glaze, which resulted in a stunning finish.

Kumazawa: It’s a beautiful brown color, almost like dark chocolate.

Mr. Ohnishi: Yes, due to time constraints, we mixed the cacao husk into our existing glaze, but if we want to increase production, we could develop a glaze based on the data from this initial firing with the cacao husk. This could lead to new, unique finishes, and I see a lot of potential here.

Kumazawa: In our collaboration, we asked you to make tiles instead of dishes. Hydro PowTech Japan plans to use these tiles in our ANY1 CHOCO store in Singapore. The sample tiles you fired are labeled “OF” and “RF.” What do these two labels mean?

Mr. Ohnishi: There are two types of firing in ceramics: OF stands for oxidation firing, and RF stands for reduction firing. In oxidation firing, we pump plenty of oxygen into the kiln, bringing out the natural colors in the ceramic. In reduction firing, we reduce the oxygen levels, causing the glaze and clay to lose oxygen, which changes the final color. With oxidation firing, there’s a chance the clay turns yellow, so Tobe’s ceramics typically uses reduction firing (RF). For this experiment, we tried both methods.

We mixed about 30% of the cacao husk into the glaze and baked it using both methods. We also experimented by adding 6%, 10%, and 12% iron to the glaze. The intriguing results produced unique colors with both oxidation and reduction firing.

Kumazawa: They look beautiful. I understand the traditional “ameyu” glaze uses iron to achieve its distinct color. The color of these oxidation-fired tiles is one of a kind. It doesn’t seem like the iron alone would create such a color; do you think the cacao husk influenced the outcome?

Mr. Ohnishi: The interaction between the iron and the cacao husk in the glaze probably created this new and unique texture.

Kumazawa: I heard the store’s tiles were hand-painted and not sprayed. The unique, uneven texture of the handwork gives the tiles character. What was it like to work with the glaze mixed with the hydrolyzed cacao husk in terms of application?

Mr. Ohnishi: It was surprisingly easy to work with, and the material seems suitable for mass production.

Kumazawa: There might be more uses besides tiles. For example, cases for chocolates or snack boxes. What do you think, Mr. Ashitani?

Mr. Ashitani: Yes, it could work as chocolate cases or boxes for snacks and sweets. After seeing the beauty of the finished product, I can imagine various possibilities, such as selling them on our company’s e-commerce site in the future.

Mr. Ohnishi: That sounds great. The glaze made with this cacao husk has a soft feel. We could achieve even more gradient effects and create more beautiful expressions with some adjustments.

Kumazawa: I’m looking forward to seeing these tiles installed in our Singapore store. Is this kind of upcycling initiative in the chocolate and confectionery industry rare?

Mr. Ashitani: I think so. There have been examples of using husks in paper, but this artistic upcycling approach is a first.

Kumazawa: For this collaboration, we asked Mr. Ohnishi to use cacao husks, but I’d also like to experiment with by-products of other foods. Are there any materials from Lotte that might be suitable?

Mr. Ashitani: Right now, we’re cultivating quince, a key ingredient for quince extracts used in throat lozenges, in Shikoku. However, once we remove the extract, what remains is practically useless. Quince contains various ingredients and is low in fat, so it might also be usable in ceramics.

Kumazawa: That sounds promising. Tobe ware is a representative piece of Shikoku, so combining these elements can engender a quintessential product that is purely Made in Shikoku. It would be wonderful to undertake initiatives more rooted in the region.

Mr. Ohnishi: Yes. Tobe ware uses over 50% local pottery stone. If we can also use citrus fruits like quince, a specialty of Ehime Prefecture, that sounds like a challenge worth undertaking.

Kumazawa: In our Singapore store, we want to showcase Japanese products while introducing examples of upcycling initiatives, reflecting the uniquely Japanese concept of mottainai (a sense of regret over waste). Since we are also a company from Niigata Prefecture, we believe in initiatives that contribute to revitalizing the region and want to emphasize communication beyond Tokyo-centric perspectives.

The allure of ceramics lies in their long-term usability. I think it’s wasteful to discard things, even if they’re upcycled. Combining inorganic and organic ceramic materials through upcycled pottery can create items that can be used indefinitely, which is fascinating. I hope this opportunity will allow us, together with Lotte and Ohnishi Ceramics, to venture into various initiatives.

Mr. Ashitani: That sounds great. Thank you.

Mr. Ohnishi: Thank you.

Kumazawa: Thank you very much for today.

(Interviewer:Kumazawa,NHP)

Lotte Co., Ltd.

https://www.lotte.co.jp/

Ohnishi Ceramics

https://www.ohnishitougei.jp/